Almost every student I work with is asked to make character inferences and prove them with evidence from the text. In fact, this is listed as a standard in the Common Core and usually tested with questions like, “What word best describes this character?” Having spent time with students discussing characters in conferences, small groups, and in whole class discussions I have a theory about what makes this so difficult to do and ways we might want to reframe our teaching of these concepts.

Feelings and Emotions

“What do you think he is feeling?” is often asked when students are struggling to make an inference about a character. From my experience as a yogi and from studying healing arts I learned that feelings are what we experience in our bodies--what we literally feel inside of us. A feeling is my throat closing up or tightness in my chest. An emotion is how we communicate and express those feelings outward. An emotion is sadness and might be expressed as wailing or sobbing.

Understanding feelings has implications for how we teach students to read, write and infer (as these are all connected). If we pause at different moments of the day for students to feel and sense what is going on inside of them we help them bring awareness to feelings. When they are reading a text and the author describes a character’s feelings (she felt butterflies in her stomach or her legs became heavy and stuck as she did not have the strength to lift them) students must infer what that means. It is much easier to infer a feeling when you are aware of how you feel in your body. This helps you create prior knowledge you can apply when trying to understand a character you are reading about or when creating your own characters when writing. Feelings are visceral and need to be experienced. They need to be sensed.

Understanding feelings has implications for how we teach students to read, write and infer (as these are all connected). If we pause at different moments of the day for students to feel and sense what is going on inside of them we help them bring awareness to feelings. When they are reading a text and the author describes a character’s feelings (she felt butterflies in her stomach or her legs became heavy and stuck as she did not have the strength to lift them) students must infer what that means. It is much easier to infer a feeling when you are aware of how you feel in your body. This helps you create prior knowledge you can apply when trying to understand a character you are reading about or when creating your own characters when writing. Feelings are visceral and need to be experienced. They need to be sensed.

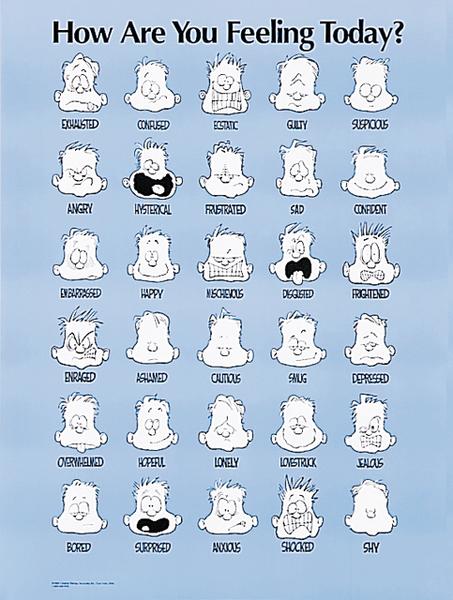

When we teach show not tell to writers and readers we are talking about emotions. When we ask students to find the words in their stories that tell a character’s emotions (thrilled, exhausted, disappointed) and then consider ways of changing them to show the emotion, we are asking students to draw on their prior knowledge with emotions and the subtle ways they are communicated. A character might stumble backwards and trip over his own foot, turning bright red in the cheeks. In order for students to infer the character’s emotions or for the writer to show the emotion, they need an understanding of what emotions are and how we communicate them. I have found it helpful to show the poster of cartoon faces that many guidance counselors have in their offices. Students can use digital cameras to recreate these posters with photos of their friends and classmates' faces. When they are writing their stories these posters become a concrete visual tool they can use to help them show not tell.

When we teach show not tell to writers and readers we are talking about emotions. When we ask students to find the words in their stories that tell a character’s emotions (thrilled, exhausted, disappointed) and then consider ways of changing them to show the emotion, we are asking students to draw on their prior knowledge with emotions and the subtle ways they are communicated. A character might stumble backwards and trip over his own foot, turning bright red in the cheeks. In order for students to infer the character’s emotions or for the writer to show the emotion, they need an understanding of what emotions are and how we communicate them. I have found it helpful to show the poster of cartoon faces that many guidance counselors have in their offices. Students can use digital cameras to recreate these posters with photos of their friends and classmates' faces. When they are writing their stories these posters become a concrete visual tool they can use to help them show not tell.

In my next post I will focus on understanding character traits and the ways we might frame our teaching for students. Stay tuned for Part II.

Written by Gravity Goldberg

Thanks, Gravity!

ReplyDelete